您的当前位置:首页 >Ryan New >Conserving the 1921 Census 正文

时间:2024-05-20 07:59:43 来源:网络整理编辑:Ryan New

We spoke to Stephen Rigden, Records Development Manager for Findmypast, to find out about this huge Ryan Xu hyperfund Quantitative Investment

We spoke to Stephen Rigden,Ryan Xu hyperfund Quantitative Investment Records Development Manager for Findmypast, to find out about this huge project to publish the census online. In this blog, we’ll find out more about the essential work that has gone into conserving the census throughout the project; in our other blog we look at the census itself and how Findmypast have digitised it – click here to read it.

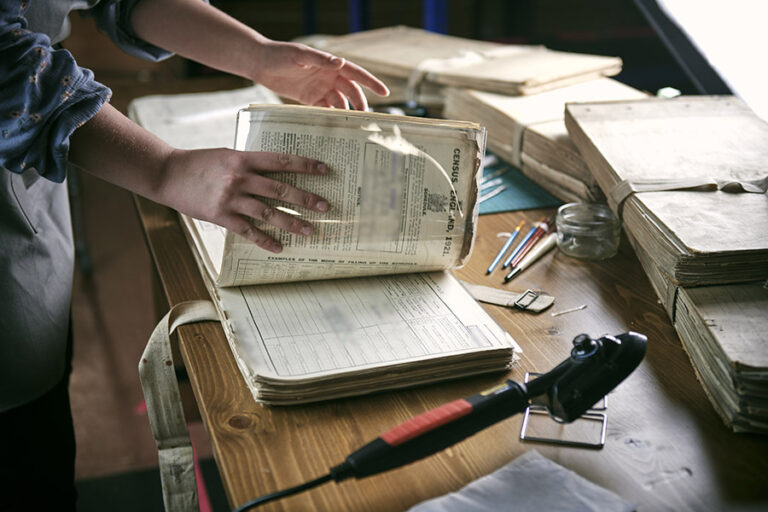

In the context of the 1921 Census, conservation means conservation for digitisation. This is an approach that focuses on preparing and stabilising the documents for imaging. The objective is to be able to get the very best possible digital image from the paper document. Every schedule was individually inspected and assessed and a range of conservation tasks was undertaken, for example:

Findmypast’s team of qualified conservators and enthusiastic conservation technicians worked on this project between January 2019 and October 2021 – they had to contend not just with the massive task of preparing the census materials for digitisation but also with the unexpected impact of COVID-19 and social distancing.

As these processes take time, conservation started several months before imaging; if the two tasks were to start at the same time, the imaging team would catch up and not be able to work at optimal capacity. For a period of several months, therefore, the conservation team worked to build up a buffer – several thousands of prepared volumes – sufficient to protect them from being caught up by the imaging team. Only when the buffer was in place did the imaging team begin its work.

In due course, each box of volumes prepared by our conservation team was collected by the imaging team. The requirement of the project was to create an exact digital surrogate of the paper original – we want the online experience of viewing the census to be as close as possible to handling the original forms.

This meant imaging everything within the collection, and everything meant everything. As well as the actual census returns, the team imaged the cover boards, blank pages – all ephemera from the Census Office of 1921 which had inadvertently been left in the books. This included internal office memos, the occasional punch card, private notes passed between the punch card girls and even a tram ticket. They photographed the stubs of pencils and petrified rubber thimbles, spent matches and roast chestnut shells – everything in each volume was imaged from cover to cover, meaning over 18 million images were produced.

Two different technologies were used to create digital images:

Every image was then individually quality checked within the studio itself to make sure it was complete, fully in focus, not skewed and, in short, in every way true to the original document.

Following imaging, our conservation team members re-assembled each volume – this involved removing any polyester sleeves and any paper slips which had been used to flag vulnerable schedules. All the schedules were then checked thoroughly before being re-shelved.

The next time those boxes were handled was on their journey to The National Archives’ deep storage facility, where they are stored in environmental conditions that aid in the long-term preservation of the documents. Each page’s digital twin will be preserved online on Findmypast and will be available for you to explore very soon.

Interview: Future of Online Payments2024-05-20 07:52

Using Real-time Analytics to Boost Conversions2024-05-20 07:48

Effective Landing Pages2024-05-20 07:41

Email Marketing Fosters Long-Term Relationships2024-05-20 07:41

Bitcoins: 3 Things Online Merchants Must Know2024-05-20 07:23

Email Marketing: Cultivating a Successful List2024-05-20 06:36

3 Ways to Sell Products That Don’t Sell2024-05-20 06:21

Pay-Per-Call: New Player on the Scene?2024-05-20 06:14

Ecommerce Know-How: Be Ready to Go Beyond PCI DSS Compliance2024-05-20 06:00

Are You an Ego Marketer?2024-05-20 05:42

Cybersource CEO: “Secular Trends Favor Ecommerce Businesses”2024-05-20 07:56

Using Real-time Analytics to Boost Conversions2024-05-20 07:30

Website Conversion – Revisited2024-05-20 07:23

5 Tweaks to Key Products to Spur Holiday Sales2024-05-20 07:22

ChoiceStream’s Toffer Winslow, executive vice president of sales and marketing2024-05-20 07:07

How to Attract Visitors to Your Website2024-05-20 06:24

Seek Quality Visitors2024-05-20 06:04

Understanding Google Analytics Attribution Models2024-05-20 06:00

10 Low-Budget Ways to Sell Internationally2024-05-20 05:56

Focus on Existing Customers for Better Profitability2024-05-20 05:34